Humans began eating grains about 75,000 years ago in Western Asia. These grains, including einkorn and emmer, grew wild near the banks of rivers and are ancestors of modern-day wheat.

People began cultivating grains more recently to the Neolithic era, which began around 12,000 years ago. During this time, humans transitioned from being hunter-gatherers to agriculturalists, and began cultivating crops such as wheat, barley, rice, and maize. Over the course of history, the way we eat grains has evolved, as different cultures and regions have developed their own culinary traditions and methods of preparing and consuming grains.

For example:

- Grinding: In the past, grains were typically ground by hand using stone or wooden tools. This process was labor-intensive and time-consuming, but it allowed for the production of flours and meal that were used in a variety of dishes.

- Fermentation: Fermentation is a traditional method of processing grains that is still used in many cultures today. It involves soaking the grains in water to soften them, then allowing them to ferment over a period of several days. This process can improve the flavor and nutritional value of the grains, and can also make them easier to digest.

- Cooking: The way we cook grains has also evolved over time. In some cultures, grains are boiled or steamed, while in others they are roasted or baked. Some grains, such as rice, are often cooked in large quantities to make a single dish, while others, like quinoa, can be cooked in smaller portions and used as a base for salads and other dishes.

- Processing: The way we process grains has also changed over time. In the past, grains were typically consumed in their whole form or ground into flour. Today, many grains are processed to create products like pasta, bread, and cereals.

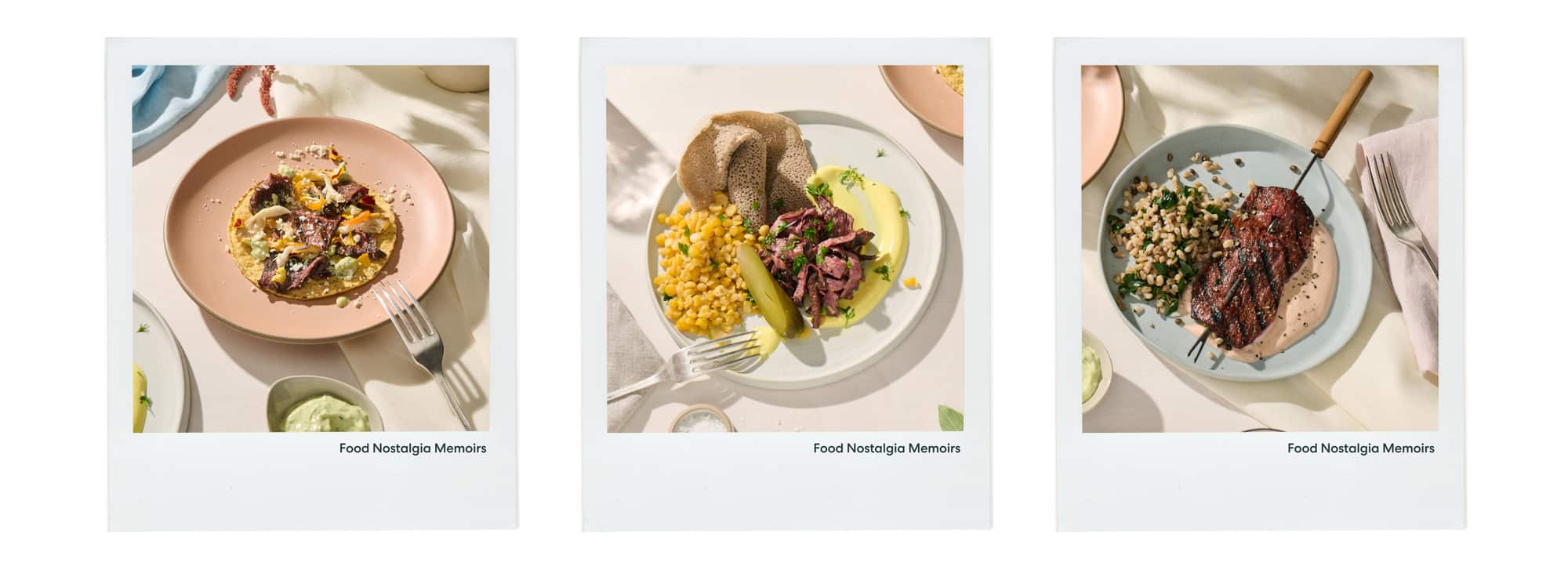

Overall, while the basic premise of eating grains has remained the same, the methods of preparation and consumption have evolved and diversified over time. Farro, corn masa and teff are just a few of the Amuse staff’s favorite ancient grains, so we dove into our pantry and decided to feature them in dishes with Aleph Cuts. We like to explore how we can preserve and celebrate food cultures and traditions through our unique product.

Farro

Pronounced FAHR-oh, and also known as emmer wheat, this sturdy, versatile, and nutrient-rich grain has a nutty flavor and pleasant chewy texture. The grain originated in the Fertile Crescent, an ancient agricultural region stretching across parts of the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East that gave rise to some of the world’s earliest civilizations.

Farro can be used in a variety of ways, from sweet to savory recipes. At its most basic, farro can make a lovely addition to soups, salads, and pilafs, but there are many more recipes that take farro above and beyond.

Corn Masa

10,000 years ago, there was no such thing as corn, just a wild grassy plant called teosinte. This plant may have resembled the corn that we know today, but it didn’t make the jump to modern-day maize until ancient farmers in what is now Mexico first domesticated the teosinte by choosing which kernels (seeds) to plant.

To this day, corn is integral to making masa (pronounced Mah-Sha), which is used to make gorditas, tamales, pupusas, and of course tortillas, one of the most essential staples in Mexican and Central American cuisine. For corn to serve this purpose, it must go through nixtamalization. Developed by the ancient Mayans, This process involves soaking and cooking corn in lime water or another alkaline solution, and then washing and hulling it.

Teff

Sometimes written as tef or t’ef, this grain is the smallest whole grain in the world, which has led some to believe that its name comes from the Amharic word for “lost.” Teff flour is used extensively in Ethiopia to make injera, a soft flatbread prepared from slightly fermented batter. The grain is also used in various stews and porridges.

As a plant, teff comes in a few color varieties including purple, gray, red, and yellowish brown. Because teff is so commonly fermented, some people mistakenly believe it has a natural sour taste. The truth is that when not fermented, teff has a light sweet taste which some have even described as nutty.

As we indulge in the delicious history of our gastronomic heritage, it is important to recognize the ways in which food technology is continuing to shape our diets. Cultivated meat is one such example, offering a sustainable and ethical alternative to conventional meat consumption. As we continue to explore the intersection of food culture and technology, it is exciting to see how we can preserve our past while also embracing new possibilities for the future.